|

Dear readers: it has been a while since I last updated my blog. We have been busy sampling and it got a bit hectic. So I could not make time to write. Internet in the middle of the Indian Ocean had not been the greatest either. I hope you did not miss the blog as much as I missed writing it.

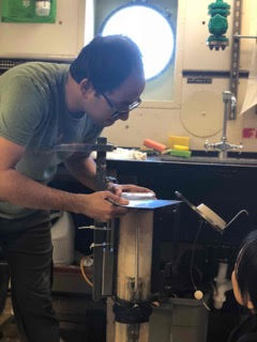

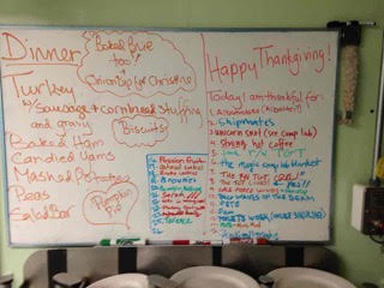

The latest update is that we are almost towards the end of our expedition. Coming up is a long transit to Fremantle and we just started our return journey. As we approach Fremantle, there is a pre-determined time and location where a ‘pilot’ will come onboard and guide us into the port. As soon as we start our transit, we have to start planning for ‘demobilization’. At the beginning of this journey, I wrote about how diligently we set up laboratory and other arrangements onboard the vessel so that we could do science without any hindrance. It is equally important to plan demobilization with utmost care. During demobilization, we have to de-construct everything and make sure that the vessel is ready for the next expedition by the time we leave. Of course, the crew will be helping us every step of the way. We also need to think about how to send our samples back to our respective home laboratories. We spent all these days collecting valuable samples, and right now the most important job is to make sure that these samples are carefully packed and send off. As we make arrangements for shipping our samples back, we have to keep in mind the export and import laws of Australia and the US. It is no trivial issue. We can only hope that we have done our homework right and the samples will travel well and show up safe and sound. I will like to thank all the participating scientists and crew members for their efforts and support throughout this expedition. And thanks to you all who followed this expedition via this blog. It was nice to have you all as audience as I narrated my experience. If you ever feel like talking about ocean, send me an email, and I will be happy to chat. On that note, I will conclude this expedition blog and hope to re-connect on a different expedition next year.  Île Amsterdam from the ship deck Île Amsterdam from the ship deck We are no longer in the Southern Ocean, and sailed past the Île Amsterdam (Amsterdam Island) yesterday. We have been sailing for over three weeks now, and have another three weeks to go before we return to Fremantle. A couple of days ago, we sailed past the Île Saint-Paul (Saint Paul Island) around 4:30 pm local time. By now you might have gotten the idea that our days are long and sometimes very stressful. So an event like this drive by has a lot of significance. Science party and crew gathered on the deck to see those islands.  Yours truly slicing mud Yours truly slicing mud Last few days have been particularly busy with lots of long and short sediment cores collected, often twice a day. Part of my research involves collecting these small cores, slicing them into 1 cm thick slices and then squeezing them to extract water that are in that mud. This water is essentially stored in the pore spaces in the mud, and we call this ‘pore water’. Studying pore water chemistry, how that affects the ocean water chemistry, and if interaction between pore water and ocean water can tell us anything about Earth’s past climate are some of the goals of my research endeavor. While it is a lot of work to squeeze mud for water, the hope is that it will help us learn something new. Many of you must have tried squeezing orange to make OJ but squeezing mud is quite different. It is messy, and tedious. Last night when we were done processing our last core, it was 3 am and we still needed to clean up the apparatus so that it was ready for the next deployment. As we were washing down the mud off the core liner out in the deck, it was a clear night with bright moon and its glittery reflection on the dark ocean. Not a bad view to end a long day.  Decorated cafeteria Decorated cafeteria Happy Thanksgiving, dear readers!! I hope you all had a wonderful thanksgiving with family and friends with loads of laughter and fun. If I am not sailing out in the Southern Ocean, my thanksgiving typically comprises of a 5K or a 5-mile turkey trot in the morning followed by a huge thanksgiving meal. This year is a bit different. It has been over a day that we have reached the Southern Ocean collecting samples at every hour of the day. So far the weather has been largely favorable, but occasional high wind and large swells reminded us what it can turn into. As busy as we are, we did get to celebrate thanksgiving onboard the research vessel. Crew members Sarah, Nikki, and Terrance are in charge of food services and they had this dinner planned well in advance so that we get to eat turkey. They requested the science party to decorate the cafeteria so that it looks a bit festive. With limited resources at our disposal, the science team immediately got to work. Thanksgiving is such an American celebration that science participants from other parts of the world had to be introduced to the story and practices of this unique celebration. I too learned how to make ‘hand turkey’. In the end, I think the science team did a good job with the decoration. The great thanksgiving dinner was to be served at 5 PM local time. My shift ends at noon and I thought to be back for dinner after a quick nap. Unfortunately, I slept through the dinner and did not reach the cafeteria until 10 PM. Luckily there were enough left over that I could still have a full meal. Even though a few hours late, the thanksgiving dinner in the high seas of the Southern Ocean tasted as good as it tastes every year.

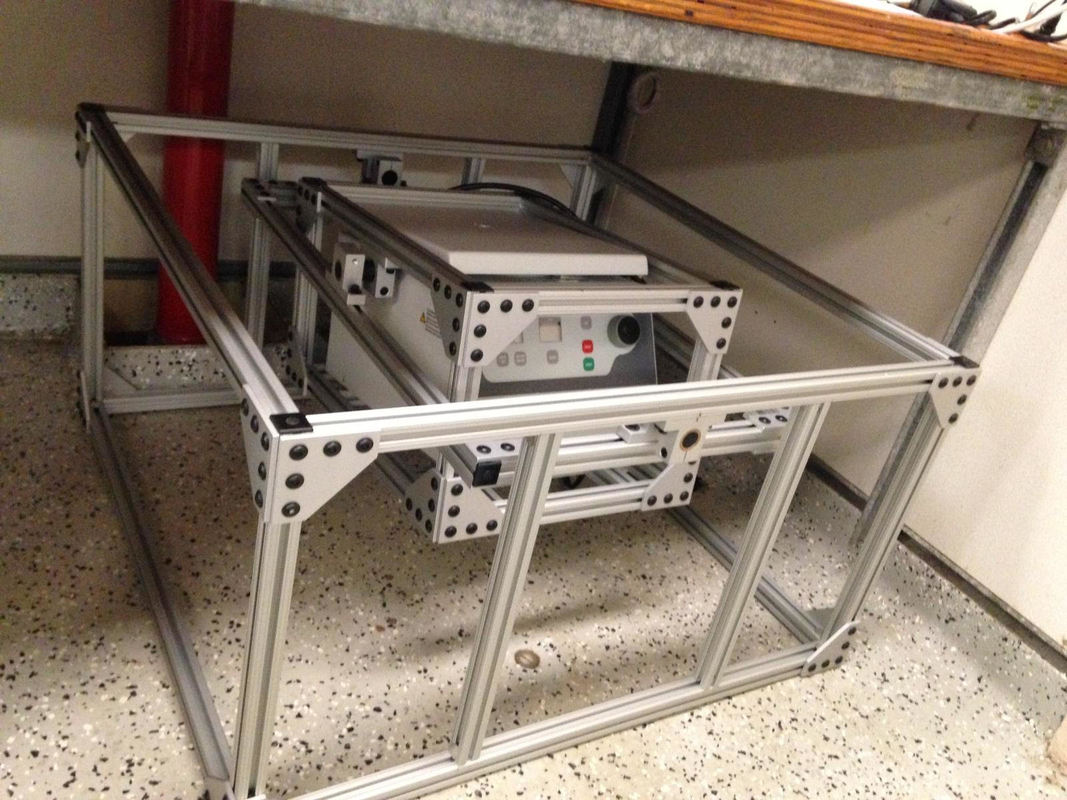

As always, I am thankful for the opportunity to do ‘Science’.  Freshly opened sediment core. This mud can tell us about past climate change. Freshly opened sediment core. This mud can tell us about past climate change. It has been almost two weeks that we left the port of Fremantle. On most days since then, each of us has been on a 12-hours 'watch'; for example, I am on a midnight-to-noon watch. During this time we work on samples that we collected, take necessary notes and describe samples in detail. Sediment/mud, once taken out from the ocean bottom, starts changing very fast as it comes in contact with the atmosphere. So we have a rather short time window to document its pristine features. As I mentioned earlier, on this cruise I am interested in water chemistry; so all my samples are primarily ocean water. These water samples also need to be filtered and acidified so that any biological organisms that are present in the water do not get to grow and change the water chemistry in the container. Much of Yingzhe's and my time have been taken up treating and processing these water samples. To do all this in a moving lab, which gives us a shake every now and then to throw us off our feet, is no easy feat. Irrespective of this non-ideal working condition, we are making progress and will be in the roaring 40s in the next couple of days.  Manganese nodule Manganese nodule Some fun things did happen in the midst of all these laboratory works. One day we spotted a whale which was moving parallel to our vessel. We all gathered at the front deck to watch, although it was a bit far to take pictures (sorry, will try next time). It was amazing to see such big and stunningly beautiful creatures that inhabit our oceans. A bird or two would occasionally pay us a visit. I find this refreshing after spending 14 days on a ship out in the ocean. We have been sampling at all hours of the day, and sampling at night is really interesting because we get to see different sea creatures. Almost every time we sampled at night, we have been fortunate because the ship’s light attracts marine creatures towards it. Another exciting event that kept us occupied is when manganese nodules were retrieved while coring for sediment. These nodules look like popcorns. Manganese nodules accrete on the bottom of the ocean and are full of.....wait for it.....Manganese as well as other valuable elements. Decades ago it was believed that those nodules could be mined for valuable minerals. A lot of researchers spent their entire career studying these nodules, but in the end it was not deemed appropriate to mine the bottom of the ocean, as the environmental impact of this mining would cause more damage than good. If you have ever taken an oceanography course and have seen pictures of manganese nodules, then the picture in this post will certainly confirm that what you learned in that class really exists. Yesterday was a long but good day. We reached our first coring station after 12 hours transit from the previous station. After arriving at the station, we started to survey the area using an instrument which uses sound waves to test the condition and nature of the mud that is at the bottom of the ocean. The goal is to find a location where mud is thick, relatively undisturbed, and would more or less represent a structure similar to a layered cake. It took about a couple of hours to find a suitable spot where we could try to deploy a jumbo piston core with the hope of acquiring long sediment cores. While the detailed mechanism of how it works is quite complicated, this coring device primarily consists of a long hollow pipe with a heavy weight at the top and is lowered to the bottom using a wire or rope. The heavy weight at the top would facilitate digging deep into the mud and fill up the pipe with sediment, which can then be pulled out and brought back to the ship. Using the layered cake analogy, you can think of this operation as putting a straw through a cake. Deploying any instrument, small or large, by the side of the boat is an onerous job. So, much of the day was spent setting up the coring device, sending it down to the ocean bottom, and getting it back on deck. Happy to report that we recovered a nice sediment core. It was almost sunset when the core was back on deck and we were just getting started. We had two more things to do before we could leave the station. One was to collect small cores using another coring device called ‘multicore’ and collect water using CTD. By the time the CTD operation was done and we finished sampling, it was close to midnight and we were ready for bed. By the way, I almost forgot to mention about Styrofoam cups. It has been a longstanding tradition to color Styrofoam cups and send those in a laundry bag(!) tied to a deploying instrument. As the cups go down to the bottom of the ocean, the weight of the water squeezes all air from these cups, and makes them small without distorting the aspect ratio. So you get a miniature Styrofoam cup. These miniature cups make great souvenirs. Next time your oceanographer friend is out on an expedition, don't forget to ask if she/he would be kind enough to bring back a Styrofoam cup for you :).

After some initial technical glitches, we have finally set sail. We left Fremantle on Wednesday, November 7, at 1600 hrs (local time). Since then we have stopped at three stations to collect seawater and mud from the ocean bottom. We arrived at our first sampling station in the middle of the night. Starry sky, cold air and sloshing waves were all there to welcome us. Before I tell you all about how we collect samples in the middle of this huge blue, let me quickly describe the mission of this cruise. The main objective of this cruise is to collect mud from the ocean bottom. This mud, or sediment as we call them, can be as old as millions of years; although the mud that we intend to collect on this cruise will not be that old. Scientists look for single cell organisms called foraminifera in this mud among many other things. Foraminifera shells are made up of calcium carbonate (chalk), and have a unique ability of storing past climate information in their shells. While I do work with these organisms, I am interested in studying ocean chemistry for this particular project. So besides collecting mud, we will also be collecting seawater at different depths.  Retrieving short cores from ocean bottom Retrieving short cores from ocean bottom Ocean can be as deep as 5000 meter (~3.1 miles) at places; so how do we collect water that deep? Scientists use an instrument called Conductivity, Temperature, Depth (CTD), which sends us information about the water properties (such as temperature, salinity) as it goes down to the ocean bottom. Also attached to this instrument is a set of bottles that can be closed from the ship's control room at specific depths. The moment we close a bottle, it captures the water at that particular depth. Where and why we want to close a bottle is something we determine based on the information that CTD sends us while going down to the bottom. Once up on deck, we collect water samples from these bottles 'fired' at the depths of our interest. Yingzhe Wu, a postdoctoral researcher from Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) is one of the participating scientists on this cruise, and we are working together on the ocean chemistry component of this project. We both had been a bit seasick since we left the port, but I think we are over it now (or I want to believe so). Since samples are coming up at a very fast pace, we are up for 18-20 hrs at a stretch so that we can process these samples and get ready for the next set of samples to be collected. I have already lost track of what day of the week it is. But we are ready for more samples in the coming days and weeks. May the Ocean Goddess/God be with us!!

I am onboard the research vessel, but we have not left the port yet. Everybody onboard is busy to make sure that we are well prepared for this expedition. So the scientists are building their laboratories and securing their scientific gear, science technicians are busy fixing their instruments, and ship's engineers are working round the clock tuning up the engine to ensure a smooth ride. With so many people onboard, it is a given that it is going to take a humongous amount of food to feed all of us for the next 48 days. Once we leave the port, there is no going back to get new supplies, so yesterday the science team helped the crew with loading food supplies. It took almost the entire day to move a truckload of food from the wharf to the ship’s pantry. At times it felt like we are in a loading dock of a supermarket. Today, the ship is scheduled for fueling which is also going to take several hours. A barge came alongside the ship to start the fueling process. You can think of this as the gas station coming to you rather than you going to the gas station. In between all these preparations, we could not forget our main objective: science. So we had a long meeting with all other science team leaders to make sure that we are efficient and productive once the samples start coming in. If everything goes well, we will be on our way tomorrow afternoon. There is a fair chance that we are going to be sailing through a marine reserve as we make our way to our first location. We will be watching out for marine mammals. So you can expect some pictures!!

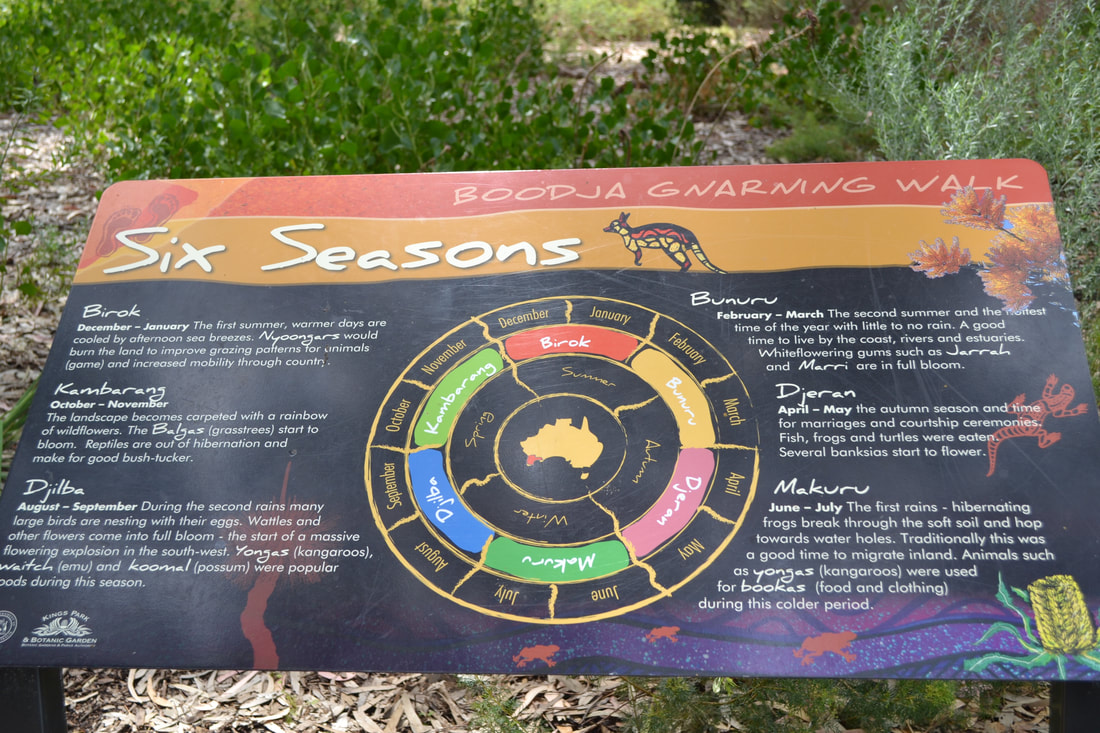

Greetings from Western Australia!! After flying for close to 24 hours I am finally here in Perth, Australia - the capital as well as the largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. I am going to stay in this beautiful city for a couple of days before heading out to Fremantle where I am going to board the research vessel R/V Thomas G. Thompson to embark on an oceanographic voyage for the next 48 days. There will be 25 scientists onboard the research vessel coming from multiple institutions from the USA, UK, and Australia. We will be using different scientific equipment to collect ocean water and mud that is found at the ocean bottom. If you follow this space for the next month and a half, you will get to know what I am up to.  World War I Memorial, Kings Park and Botanic Garden World War I Memorial, Kings Park and Botanic Garden Meanwhile, I have been walking in and around the Kings Park and Botanic Garden - one of the major parks in Perth. This park is close to 1,000 acres and is larger than the Central Park in NYC. Overlooking Perth’s business district, this beautifully maintained space is refuge to numerous native plants, indigenous fungi, and bird species. It is spring time in Western Australia, so wildflowers are in full bloom. With sunny and beautiful weather, it was nice to walk along the eucalyptus scented walkways and look at the rich biodiversity.

|

AuthorChemical oceanographer, Paleoceanographer, Chef-in-my-kitchen.......not necessarily in that order. Archives

December 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed